by LaGuardia’s Nutrition and Culinary Management Program/Health Sciences Professor, Dr. Nicolle Fernandes

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Dr. Nicolle Fernandes

Dr. Nicolle Fernandes is an Associate Professor and Director of the Nutrition and Culinary Management Program within the Health Sciences Department at LaGuardia Community College. She began teaching at LaGuardia in 2014. She received her Ph.D. in Nutrition from Texas Woman’s University in Denton, Texas and worked on d-δ-Tocotrienol-mediated cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in human melanoma and prostate cancer cell lines. She completed her postdoc at Nestlé Nutrition R&D Centers in Hopkins, Minnesota and worked in the Aging Care platform. Dr. Fernandes is also a Registered Dietitian through the Commission on Dietetic Registration, the credentialing agency for the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics in the Unites States and in India through the Indian Dietetic Association. She was a practicing Dietitian in India and began teaching there in 2003 at the Institute of Hotel Management, Catering Technology and Applied Nutrition in Dadar, Mumbai. Her research interests include impact of nutrition in cancer, obesity, falls and fracture in the geriatric population, herbs and spices, culinary nutrition, hunger, food insecurity and sustainability in the food arena.

Bread has been fundamental in nourishing mankind for centuries. Moreover, its associated-connotations, spanning cultures across the globe, marks its prominence and significance throughout history. Bread made its original debut sometime after the transition from the Paleolithic era (hunter gatherer) to the Neolithic era (agriculture). The oldest record of bread-making was identified in ancient Egypt in 1300‐1500 BCE and China in 500‐300 BC. Ancient Greeks subsisted on a bread made from barley whereas amongst ancient Egyptians wheat flour was used by the rich, barley by the middle class, and sorghum by the poor. In fact, the workers who built the pyramids in Egypt are documented to have been paid in bread. Romans feasted on the more exclusive and expensive white (refined) bread, which we know now, is less nutritious. Additionally, in medieval Europe, besides being a nutriment, stale bread termed trencher, was used as plates that was either eaten (as it softened with exposure to moistened foods), collected for the poor, or fed to the dogs after the meal.

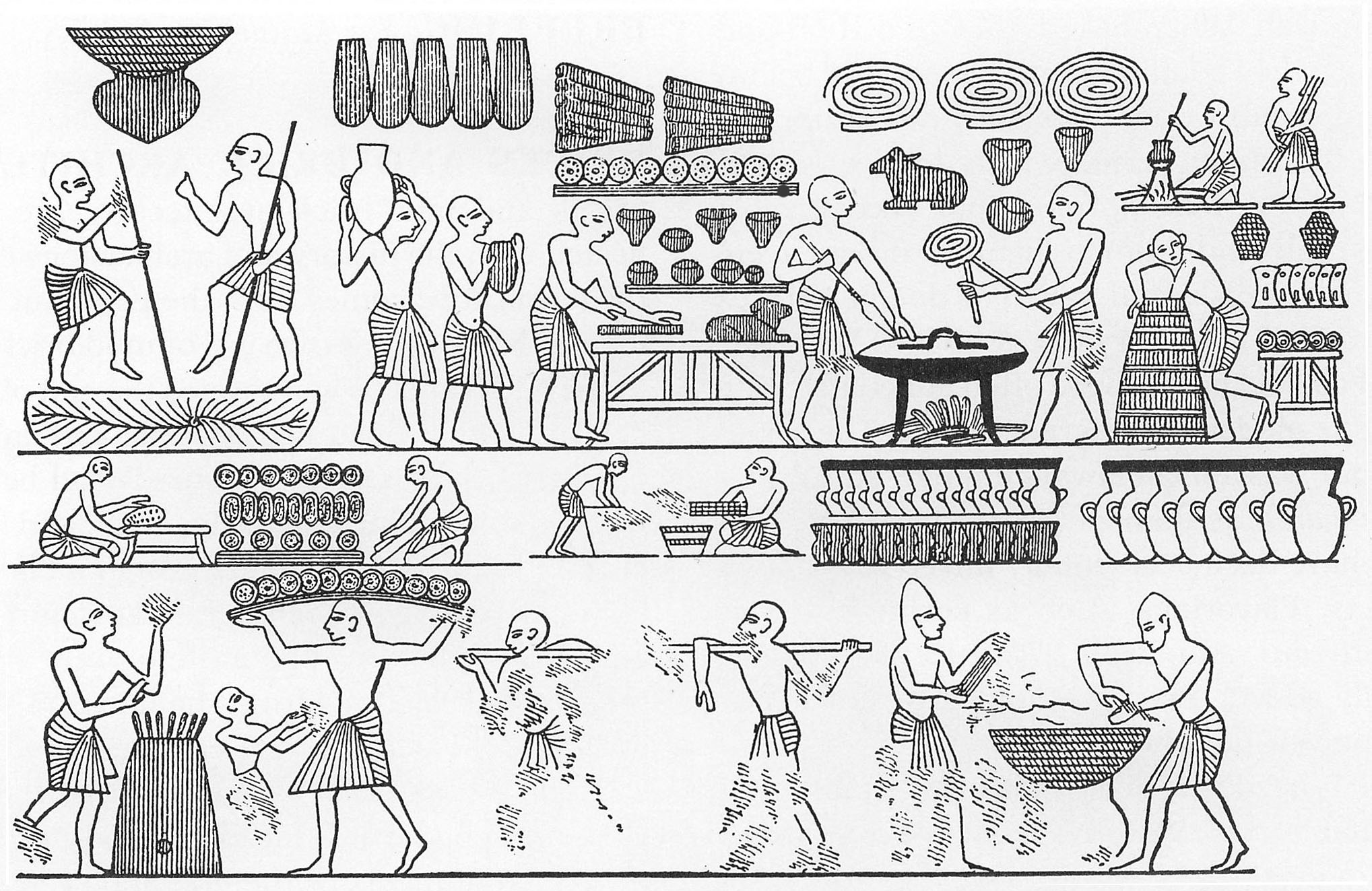

The court bakery of Ramesses III. “Various forms of bread, including loaves shaped like animals, are shown. From the tomb of Ramesses III in the Valley of the Kings, Twentieth Dynasty of Egypt.” Image Credit: http://www.historicalcookingproject.com

More modern connotations associated with bread exist such as the term “bread-winner” referencing the economic provider for the household. In Russia in 1917, the Bolsheviks promised “peace, land, and bread.” In India, life's basic necessities are referred to as “roti, kapda aur makan” (bread, cloth, and house). In France, the “Breadbasket” is a term that identifies a region that supplies a bountiful harvest. In Europe, guests are welcomed with bread and salt. In Christianity, Jesus identifies himself as the “bread of life” and the Eucharistic celebration involves the symbolic use of bread and wine. The expression “to break bread with someone” means “to share a meal with someone.” History attributes this idiom to Marie Antoinette, wife of King Louis XVI, “Don’t have bread, eat cake!” The words “dough” and “bread” are used synonymously with money in English-speaking countries. For instance, a remarkable or revolutionary innovation may be called the best thing since “sliced bread.”

Around the world today, bread continues to be enjoyed and depicts an innate cultural identity. In Ethiopia, Injera is a popular sourdough-risen flatbread, and in South Asian countries, Naan is the leavened, oven-baked flatbread consumed. Vánočka is a sweet bread studded with raisins and topped with almonds and sugar enjoyed in Czech Republic and Slovakia; Zopf is a rich and buttery yeast bread that is either twisted or braided and served in Swiss, Austria or German; and, Pita is a yeast-leavened round flatbread from the Middle Eastern and Mediterranean regions. Tortilla is the round, thin, flat bread of Mexico made from unleavened cornmeal or, less commonly, wheat flour and Roti and Chapati are Indian unleavened flat breads. Qistibi is a traditional dish in Tatarstan (Russia) ‐ a baked flatbread with a filling inside, while Obi Non is a yeast leavened flat bread popular in Afghan and Uzbek cuisine. Irish soda bread uses sodium bicarbonate or baking soda as the leavening agent instead of yeast. There are 3,200 officially recognized types of bread in Germany per the bread register of the German Institute for Bread. United States is credited for Banana bread, Corn bread, Fry bread and Texas toast among others.

Traditional injera from Ethiopia: Recipe and Traditions from the Horn of Africa. Photo by Peter Cassidy/Image courtesy: https://nationalpost.com

Left-side image: Qistibi is roasted flatbreads with various fillings inside. Image Credit: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Qistibi; Right-side Image: Traditional Czech sweet bread called Vánočka is sold all year round in the Czech Republic, but Czechs mostly buy and eat it on Christmas morning with a hot cup of káva (coffee) or čaj (tea). Image Credit: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vánočka

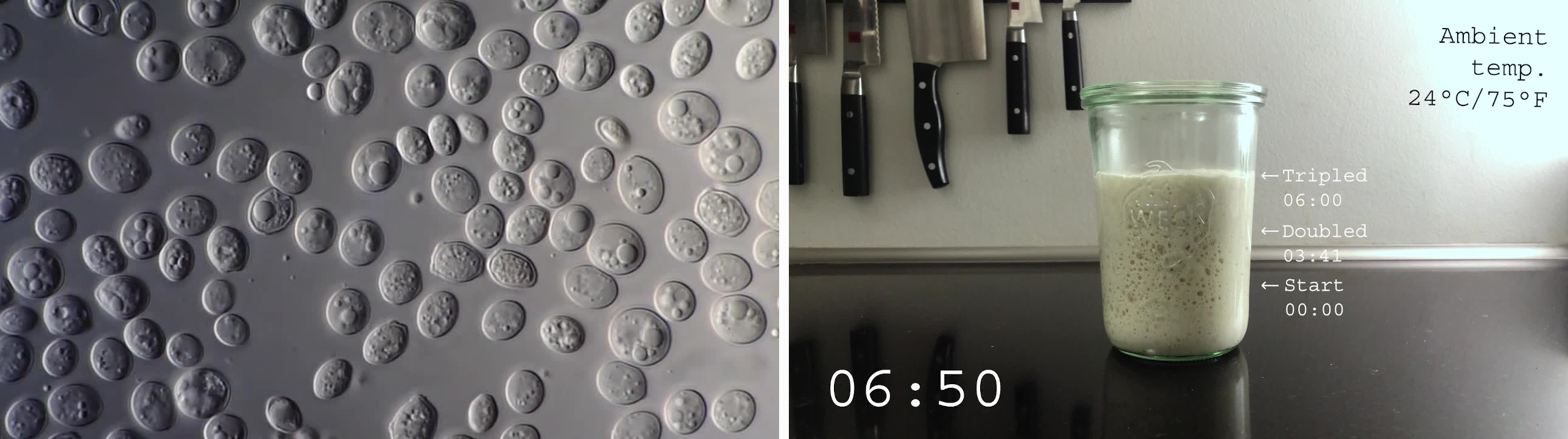

Sourdough is a special type of slow-fermented bread that uses a live fermented culture thought to have originated in the Fertile Crescent, a crescent-shaped region in the Middle East, spanning Egypt, modern-day Iraq, Israel, and Jordan, and is believed to have occurred by accident. Sourdough starter, in place of a commercial yeast (ex. Saccharomyces cerevisiae) is commonly used in conventionally leavened breads. A sourdough starter begins as a simple mixture of flour and water and because microbes are ubiquitous in nature, with the passage of enough time (between days 10-15) it ends up teeming with a unique microbial community, predominantly lactic acid bacteria (LAB) and fewer acid tolerant yeasts. Initially, the starter is open to any and all microbes; however, as the microbes begin the fermentation process, they digest the flour breaking down large starch molecules into simple sugars. The LAB break down the simple sugars into carbon dioxide and acids such as lactic acid and acetic acid (lactic acid fermentation) whereas yeast feed on the simple sugars releasing carbon dioxide and alcohol (alcohol fermentation).

Left-side Image: Yeast Saccharomyces Cerevisiae - DIC microscope 1000x/Image courtesy: Youtube channel: TheMicrobiology09; Right-side Image: A healthy sourdough starter grows insanely high/Image courtesy: Youtube channel: Foodgeek

The production of lactic acid by LAB lowers the pH of the starter thereby deterring the growth of subsequent and potentially harmful bacteria whilst creating a favorable environment for the yeast. The lactic acid also imparts the characteristic sour flavor profile to the bread. In addition to the variability of the starter culture, other factors that contribute to the distinguishing features of the sourdough bread include human culture, geography, individual baker, type of grain/s used, timing of sampling in the starter’s history, temperature, etc. This is exactly what makes Sourdough bread exciting to prepare; the resultant is a unique bread with a distinctive flavor profile and texture despite the use of standard ingredients.

Fermentation is a process in which microbes that possess a unique set of metabolic genes, code for specific enzymes that break down distinct types of starch or sugars into metabolites such as alcohols and acids.

Sourdough fermentation also contributes to the enhanced nutritional profile of Sourdough bread when compared to other yeast-bread counterparts in terms of mineral bioavailability, antioxidant properties, digestibility, and deferred starch bioavailability which facilitates glucose control. For instance, the acidic pH rendered by LAB in sourdough bread denatures phytate, an anti-nutritional factor commonly found in grains and seeds, and known to bind to minerals such as iron, zinc and magnesium resulting in their elimination from the body. Sourdough fermentation can reduce phytate content up to 50%, significantly increasing mineral bioavailability. Studies have also reported the production of antioxidant peptides from grain proteins by sourdough LAB, providing protection from free radicle damage. In relation to digestibility, while the live microbes (probiotics) in the sourdough starter do not survive the baking temperatures of bread, they positively influence the gut microbes by producing non-digestible polysaccharides during fermentation. These prebiotics help sustain the beneficial gut bacteria in the human body. Sourdough fermentation has also been noted to degrade gluten to some extent, rendering it more comestible for people with milder to moderate gluten sensitivities. Promising for diabetics, studies have shown sourdough bread consumers to have lower blood glucose and insulin levels compared to baker’s yeast bread consumers. This is attributed to the restructuring of the starch molecule during fermentation that delays glucose entry into the bloodstream. The release of organic acids during fermentation also tends to delay stomach emptying further adding to glucose control.

Tartine Country Bread considered the holy grail of sourdough bread by LaGuardia Professors Poppy Slocum (left image) and Roman Senkov (right image). Photo Credit: Ad Astra Newsletter

Given the many benefits and the ancient connection, would you like to consider giving it a try and making your very own sourdough bread? Well, you won’t need to get your hands sticky since there is no kneading required nor do you have to own a bread machine or stand mixer. Just be willing to patiently wait for the wild yeast unique to your environment work its magic and enjoy its tangy flavor, chewy texture and crisp, crackly crust. Check out some recipe links provided below. Don’t forget to share your pictures (and sourdough starter proportions) at Ad Astra Gallery.

There’s more! If you wish to get plugged into an international project, enter your sourdough recipe into a sourdough database to share with the world using the following link https://www.questforsourdough.com/sourdough/wizard managed by the Puratos Center for Bread Flavor, Belgium. The project titled “The Quest for Sourdough” aims to preserve baking knowledge and sourdough heritage and currently holds 124 actual sourdoughs from bakers all over the world... with plenty of room for more! Explore more at https://www.questforsourdough.com.