by Edda Monique Ottilie Proenca Hobuss

The work was done under the supervision of Dr. Ting Man Tsao as a part of the ENG101: Composition I course in the Spring 2021 semester.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Edda Hobuss

My name is Edda Monique Hobuss and I'm a freshman Physical Sciences student at LaGuardia Community College. I'm a member of the President's Society, and of the STEM club. I plan to transfer to a four-year college after graduating in Fall 2022 to finish my studies in Physics. I love science and science education, and when I'm not learning, I'm reading or walking around the city.

Strolling through Jackson Heights, you hear many more languages and dialects than you can count – from Spanish to Hindi, from Brazilian Portuguese to Nepali, from Pakistani to Cantonese, and anything in between. You may also eat Mexican tamales while drinking Japanese matcha for breakfast, snack on Indian samosas for lunch, and have Colombian bandeja paisa for dinner while seeing passersby wearing anarkalis, hijab, and jeans. This multicultural and busy neighborhood is located in the borough of Queens in New York City. It is here where my husband grew up, where we met, and most importantly, where we have been living since we got married. Like many in the area, we share a small studio apartment with my in-laws. And even though they do not speak English well and my Spanish is close to terrible, we make it work and when it does not, laugh about it.

In 2020, we were living our lives as usual and getting excited about the warming weather around March when Jackson Heights suddenly lost its spark. People were worried about a virus that came from a city called Wuhan in China. This virus was popping up everywhere around the world, not only making people really sick, but also killing many. With every passing day more stores would close, and fewer and fewer people and street vendors were around. We live two blocks away from Elmhurst Hospital and I remember hearing ambulance sirens non-stop at any time of the day. But during the night, the sound of helicopters would overpower it and fill the air of our tiny apartment. The country sent doctors and medical supplies to Jackson Heights to help us out of the hell we had fallen into. Our neighborhood was called “the epicenter of the epicenter” by doctors and news anchors. COVID-19 had reached us and put Jackson Heights on the map for the worst reasons.

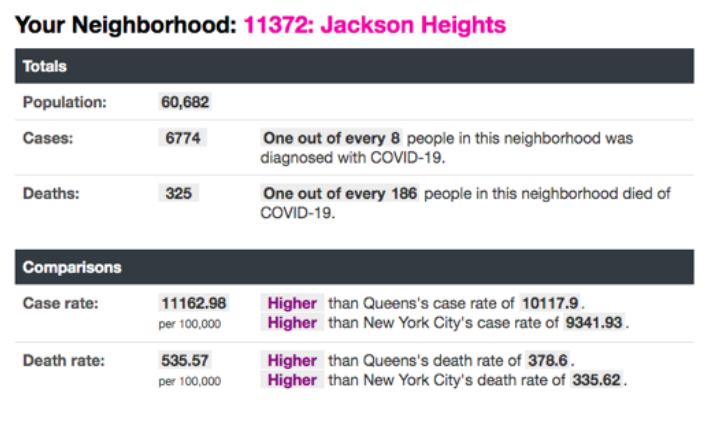

SARS-Cov-2 is a coronavirus that, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, spreads mainly through respiratory droplets between people in close contact with others. Although most infected people get only mild symptoms such as fever, cough, runny nose, shortness of breath, and loss of smell, some show no symptoms at all. On some occasions, though, the virus can cause severe illness and even death. Today, May 6th, 2021, the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene reports that Jackson Heights’ death rate stands at 533.92 per 100,000 residents and the case rate at 11,075.64 per 100,000 residents, as seen in Fig.1. Jackson Heights’ case rate is 10 percent higher than that of its borough, i.e. Queens, and 16.5 percent higher than that of the city as a whole. The death rate is even worse: it is 38 percent higher than the citywide counterpart. Compared with that of Manhattan, a much richer and healthier borough, Jackson Heights’ death rate appears all the more tragic, being 67.15 percent higher. But why? What went wrong? Was it simply due to underlying health conditions? Was it because the majority of people in Jackson Heights were considered essential workers right at the beginning of the pandemic and forced to keep working, taking trains and buses while everyone else was protected in quarantine? Or was it because the majority of us did not have health insurance and only went to the hospitals to die?

Figure 1. Jackson Heights’ COVID-related data (as of May 6th 2021). |

To answer these questions, we need to look at my neighborhood's pre-pandemic health conditions. Months before the virus even got to the country, Jackson Heights was considered a relatively healthy neighborhood compared to the rest of the city. According to New York City Department of Health’s Community Health Profiles 2018, 86 percent of its residents had a healthy diet, eating at least one serving of fruit or vegetable a day. The report also indicates that they do not exercise any less than other New Yorkers, specifically 72 percent in both cases reported not getting any physical activity in the 30 days prior to answering the survey. Additionally, the survey results indicate that only 28 percent of adults had no health insurance, a number I disagree with as I personally do not know anyone who is insured. In fact, Latinos, Asians, and Blacks – especially those who are undocumented—are historically mistrustful of surveys and extremely cautious about sharing their information. This means that data provided by the Census and the New York City Bureau of Vital Statistics, although pointing in the right direction, might sometimes hide conditions the government has been disregarding or underestimating. It is possible that a large number of undocumented immigrants who are not insured are also not included in these data.

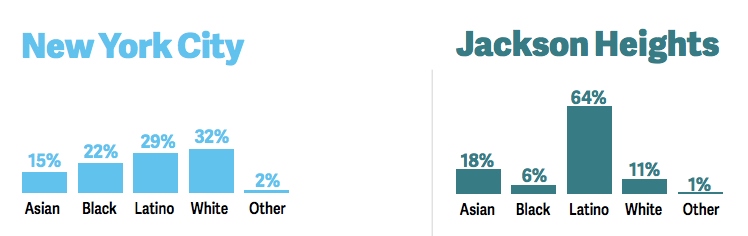

Figure 2. Racial and ethnic makeup of New York City and Jackson Heights. |

Jackson Heights is notably one of the largest immigrant neighborhoods in the city, as illustrated by Fig.2. According to the Community Health Profiles, 64 percent of Jackson Heights’ residents are Latinos and 60 percent were born outside of the United States, but it does not mention how many are undocumented. Of course being a foreigner is not uncommon in New York City. After all Emma Lazarus called it the home city of the “Mother of Exiles” with her “golden door” always open for immigrants. For instance, 76 percent of residents in Hunts Point and Longwood in the Bronx are Latinos, and 54 percent of Flushing’s residents in Queens are Asians. What undoubtedly stands out about Jackson Heights is the fact that about half of its residents have limited English proficiency. This is an indication that the neighborhood is made out of new immigrants, and this fact bears a unique relation with poverty, education, housing, and employment opportunities.

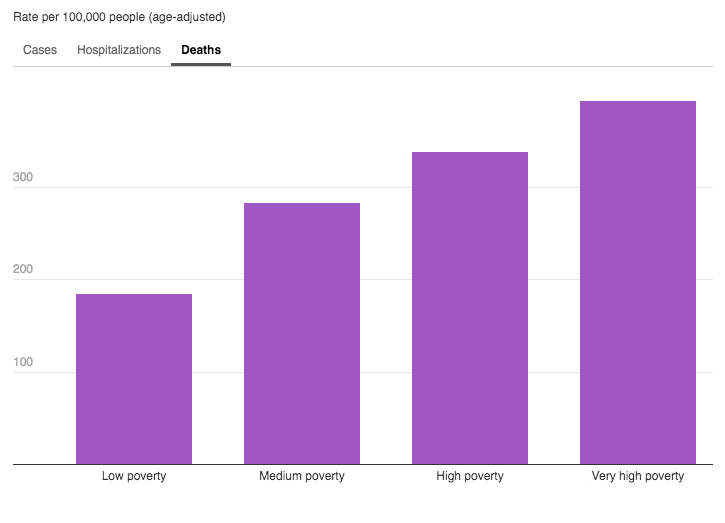

Poverty among its residents is important to our understanding of how COVID-19 devastated Jackson Heights. As stated by the Community Health Profiles, 25 percent of its residents live in poverty, compared with 20 percent of New York City residents. Living in poverty does not only mean having little to no money but also limited access to such necessities as food, shelter, and clothing. Tellingly, the poverty in Jackson Heights is not caused by a high unemployment rate. The same report indicates that the unemployment rate of this neighborhood lies as low as that of Manhattan at 7 percent whereas New York City’s overall rate stands two percent higher at 9 percent. What this data reveals is that the majority of Jackson Heights’ residents are “working poor,” i.e. families and individuals who are regularly employed but are not paid a living wage. They have to work long hours to be able to survive, but they do not earn any sick leave or make enough to eventually escape poverty and thereby the impact of the pandemic. As seen in Fig. 3 from the New York City Department of Health’s COVID-19 Data, the crisis had a devastating and disproportionate impact on low-income neighborhoods like Jackson Heights.

Figure 3. COVID-19 death rates by socioeconomic groups (as of May 6th, 2021) |

Education is one of the contributing factors in my neighborhood’s poverty. According to the Community Health Profiles, only 27 percent of adults in Jackson Heights have a college degree and an astounding 30 percent have not even finished high school. It is well known that most white-collar jobs require at least a university diploma. Add this to the fact that half of the people in the area do not speak the official language of the country well and you will end up with a neighborhood filled with unskilled and semiskilled workers who are putting in long hours but still cannot make ends meet. Therefore, this lack of education not only limits people’s access to stable, well-paying jobs but also impacts their health outcomes and choice of housing.

Poorly built and maintained housing is notably associated with exposure to lead, asthma triggers, and mental health stressors. As reported by the Community Health Profiles, half of the renter-occupied homes in Jackson Heights suffer from heating breakdowns, cracks, holes, peeling painting and other defects. Fifty-nine percent of its residents spend more than 30 percent of their income in housing, compared with 51 percent citywide. Devoting much of their income to rent, these residents struggle to meet basic needs such as food, clothing, transportation, and health care. As a result of poverty and rent burden, many end up sharing apartments with their families and other people. For example my husband’s goddaughter Evy lives with her parents in a room in an apartment they share with three other families. All of them, except the children, are undocumented. As far as I know, seven to nine people live in this three-bedroom apartment; that means about 2.5 people sharing a room. And during the lockdown, this was a recipe for disaster.

In April 2020 when the whole city was locked down for quarantine, many of these undocumented immigrants were considered “essential workers.” And although most of them continued filling the shelves of your supermarkets, delivering your groceries and takeout orders to the comfort of your home, and even cleaning the hotel where you had to quarantine in, they do not qualify for health insurance or unemployment benefits. As a result of that, the majority of people did not have a choice other than continuing working, even when sick. And of course they were risking their, their families and their housemates' lives at the height of the pandemic. What makes it all the more sad is that though these residents are also considered “people of color,” to this day they are only mentioned in footnotes in the news about the uneven impact of COVID-19 on Black communities.

At the peak of the pandemic, Jackson Heights’ residents crammed into overcrowded apartments worrying about their work, rent, and food, all the while seeing family members and acquaintances fall ill and lose their lives. The low education and English proficiency levels, compounded with precarious immigration and economic status, caused an unfortunate housing situation and limited access to basic resources that promote health. Jackson Heights was a house of cards that just needed the slightest breeze to fall. Right now, according to the New York City Department of Health, Jackson Heights is half fully vaccinated and on its way to recovery. We are slowly coming back to normal – a bit hurt and a bit different, but definitely stronger and wiser. I hope that the city learns from its mistakes and addresses the inequities discussed in this article to improve the health outcomes of this amazing multicultural neighborhood I call home.

Afterword:

Since the writing of this article, the New York City Department of Health has acknowledged that systemic racism played a key role in the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on underserved communities such as Jackson Heights. In response to this, they have created a comprehensive Equity Action Plan, implementing “a racial justice framework and population-specific strategies to better reach community members” (Overview).

The pandemic is still not over, and many mutations are being discovered. However, Jackson Heights is among the neighborhoods that have the highest vaccination rates in New York. 99.9% of its residents have already received at least one dose of the vaccine, and 93.7% are fully vaccinated.

This new development shows that the city has indeed committed to change for the better. I am hopeful that my neighborhood’s families will thrive not only in health, but also in education and economically so that we will remember this chapter as a wake-up call.

Works Cited

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID-19 and Your Health. 11 Feb. 2020, https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/faq.html. Accessed 6 May 2021.

New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. Community Health Profiles 2018. https://a816-health.nyc.gov/hdi/profiles/. Accessed 6 May 2021.

New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. COVID-19 Data: Neighborhood Profiles. https://www1.nyc.gov/site/doh/covid/covid-19-data-neighborhoods.page. Accessed 6 May 2021.

New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. Overview of the NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene’s COVID-19 Equity Action Plan. 5 June 2020.