by Danielle Fisher

This work was done by LaGuardia student Danielle Fisher under the supervision of Professor Jessica Kindred (Developmental Psychology, SSY240)

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Danielle Fisher

Danielle Fisher is currently pursuing admission to the Licensed Practical Nursing (LPN) program. Her long-term goal is to earn an Associate’s Degree in Nursing and, eventually, a Bachelor’s Degree in Nursing. Passionate about understanding the brain and caring for others, she aspires to become a Neuroscience Nurse in the near future.

In the Fall Term 2023 Session II Developmental Psychology course, I was assigned to select a theorist I considered intriguing and immersed myself into their perspective by “Being Them.” This diary entry is my reflective journal, as Donald Olding Hebb. He was born on July 22, 1904, in Chester, Nova Scotia, Canada. His lifelong fascination with the relationship between neurons and cognitive functions, such as learning and memory, positively impacted the field of neuropsychology.

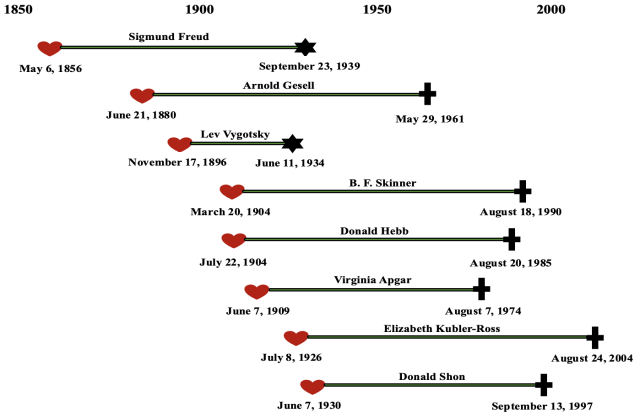

After choosing a theorist, I was grouped with other students who had also selected their theorist of choice, and we exchanged information using the first-person perspective, “I” voice. Before the end of the session, I was instructed to write a journal or diary entry reflecting on my selected theorist and the possible interactions and similarities with theorists chosen by my classmates. Additionally, I was tasked with developing a timeline visually representing the birthdates of the theorists I interacted with in class.

My reflection on the journey of becoming Donald Olding Hebb is included at the end of this paper. As a result of this exercise, I developed a more thorough understanding and appreciation of Hebb’s life, his theory, and his contribution to the field of psychology today. Furthermore, this interactive and thought-provoking learning activity helped me understand various theorists beyond just the one I selected.

My name is Donald Olding Hebb. I was born on July 22, 1904, in Chester, Nova Scotia, Canada. My parents are Arthur Morrison Hebb and Mary Clara Olding Hebb. They are both physicians who graduated from Dalhousie University. I am the eldest of four siblings: myself, Andrew, Peter, and Catherine. I have been married three times. I have two lovely daughters with my second wife, Elizabeth Donovan. Their names are Jane and Mary Ellen.

I graduated with a B.A. in English from Dalhousie University when I was 21 (1925), hoping to become a novelist. At 22, after reading Freud’s work, my life took on a different direction. While I found Freud’s theory intriguing, I realized I needed to delve deeper to understand it. So, in 1927, when I was 23 years old, I decided to apply to graduate school for psychology at McGill University in Montreal. The following year, I was accepted as a part-time graduate student at the university. After earning my masters degree in 1932, I pursued a Ph.D. at Harvard University which I completed with the leading physiological psychologist, Karl Lashley, in 1936.

I have devoted much time researching the correlation between environmental factors and experiences that influence the brain's structure and functions. I made significant contributions to the field of neuropsychology. My groundbreaking book, “The Organization of Behavior: A Neuropsychological Theory,” published in 1949, defied the trend separating cognitive processes from the neurophysiological foundation. I developed the Hebbian theory about the process of learning. It explains a fundamental principles of how neural connections are strengthened through repeated stimulation or, as I explained in my book, “[w]hen an axon of cell A is near enough to excite cell B and repeatedly or persistently takes part in firing it, some growth process or metabolic change takes place in one or both cells such that A’s efficiency, as one of the cells firing B, is increased” (Hebb, 1949, p.63). This idea is often summarized in a statement: “Neurons that fire together, wire together” (Keysers & Gazzola, 2014). In short, I proposed that our brain’s biology changes as a result of experiences.

Meeting 7 Theorists Through Other Students

Dear Diary,

I have had the most incredible opportunity to encounter and learn from seven interesting theorists who revolutionized our understanding of developmental psychology. Their theories have inspired other theorists, like me, to explore related topics, leading them to discover answers to their inquiries. I have written about them based on their respective ages. I’m so excited to share my thoughts about them with you.

I was honored to meet the man who would shape my path toward a deeper purpose in life, Sigmund Freud, the father of psychoanalysis (Pintado, 2024). He was born on May 6, 1856, and died on September 23, 1939. He would have been 48 years old when I was born. I recall reading his work when I was 22 while harvesting on a farm in Alberta and laboring in Quebec. I aspired to be a novelist, but little did I know that reading Freud’s work would eventually lead to a greater purpose in my life. His psychoanalytical theory suggests that our mind is composed of three parts: the id which acts on the principle of pleasure, the superego that functions on the principle of morality and ideal, and the ego which serves as the mediator between the two and functions on the reality principle. In my book, “The Organization of Behavior,” I've stated that his understanding of the mind as interacting id, ego, and superego help us understand and articulate human behavior. He believed that hysteria, then the most commonly diagnosed mental disorder, stemmed from the mind rather than the brain. He encouraged patients with hysteria to express their thoughts without having to filter them. This allowed Freud to tap into his patients unconscious mind and help them understand the source of their struggles, and possibly resolve them. Although Freud has made a significant contribution to psychology, I felt his work lacked accuracy and needed to be studied thoroughly. I knew that there is a deeper explanation for how we develop and behave. This realization came from understanding the importance of studying the brain. People were apprehensive about learning about the brain due to its intricacies. As for me, I wanted to unfold the mysteries of the brain.

A pioneer in child development Arnold Gesell brought his theory of maturation to my attention (Ko, 2024). He was born on June 21, 1880, and died on May 29, 1961. He would have been 24 years old when I was born. As the oldest of four children, he was able to observe their development and became interested in learning about it further. I found it amusing that his theory of maturation or developmental milestones suggests that children develop uniformly, and acquire the skills in invariable sequence. This reminds me of my theory and how it relates to learning. I believe that children need to be in a stimulating environment to achieve their highest potential so they can proceed into adulthood with an ongoing ease of acquiring new information. Gesell immersed himself in the center of human biology by delving into topics like the nervous system, much like me. We both believe that a combination of both our biology and environment is essential. Furthermore, if I had accepted the offer of pursuing my Ph.D. at Yale University in 1934, there would have been a chance of meeting him since he was head of the Clinic of Child Development from 1911 to 1948 at Yale School of Medicine.

I resonated strongly with the sociocultural theory of Lev Semionovitch Vygotsky, the father of cultural-historical psychology (Jacome, 2024). He was born on November 17, 1896, and died of tuberculosis on June 11, 1934. He would have been 8 years old when I was born. I experienced tuberculosis of the hip when I was 27 years old in 1931 and was bedridden for a year. Although I managed to recover, it left me limping for the rest of my life. Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory addresses predominantly cognitive development. He suggested that we learn through engaging in social interactions. He believed that social interactions and culture have a significant role in cognitive development. A child gains the advantage of being surrounded by adults who are good role models and are likely to acquire knowledge from them. As I think about his theory, it’s interesting to recognize its similarity to my understanding of the importance of an enriched environment for a child to learn, such as having regular conversations, which develops neural connections for speaking and expressing ideas over time. While our theories differ in many ways, we share our interest in understanding human development.

B. F. Skinner, known as the father of operant conditioning, was born on March 20, 1904, and died on August 18, 1990 (Jordan, 2024). We were born the same year, I, being 28 days older than he. Interestingly, we had similar majors; he graduated with a B.A. in English Literature, while I graduated with a B.A. in English. We both aspired to be novelists but shifted our focus to studying psychology. Our theories focused on behaviorism and were influenced by the theorist Ivan Pavlov. Skinner’s theory on operant conditioning suggests that we utilize rewards and punishment to change peoples’ behavior. I must admit, I did not realize it. However, I believe that I approached my theory of development more holistically and managed to include different aspects of behavior, such as learning, perception, and attention. Skinner earned his Ph.D. at Harvard University in 1931 and remained there for five years. (I transferred to Harvard University in 1935.) At some point in my life, as I became familiar with his work I became aware of our shared interest in learning. I even included him in the bibliography of my book, “The Organization of Behavior” (Hebb, 1949). I believe that if we had met at Harvard University, we could have exchanged valuable insights about human behavior.

Virginia Apgar was an impressive researcher who made a lasting impact as an obstetrical anesthesiologist and physician (Khakimova, 2024). She was born on June 7, 1909, and died on August 7, 1974. I was only 5 years old when she was born. My mother (the third woman to receive an MD from Dalhousie University, Nova Scotia, Canada) and Virginia were both physicians during the early 1900s, when it was rare for women to work in such a position. In 1952, when she was 43, she developed the Apgar Score, the assessment tool used worldwide to evaluate the newborn's status. APGAR, her last name, in this case stands for Appearance, Pulse, Grimace response, Activity, and Respiration. The Apgar score ranges from 0 to 10 and is assigned twice to a baby, one minute and then again five minutes after birth. A score of 7 and above suggests normal development (ACOG Committee Opinion, 2021). Anything below 7 means a baby needs more medical attention, and may have a higher risk of developmental complications. I am glad the Apgar score was developed because a baby who may not meet the score of 7 and above will be provided with essential interventions. This intervention may prevent lifelong disabling effects that could impact development of a child.

An encounter with Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, a pioneer in near-death studies, was deeply moving to me (Kim, 2024). She was born on July 8, 1926, and died on August 24, 2004. I was 22 years old when she was born. In addition to several losses in her life, she also experienced a near-death experience as a prematurely born baby. Her personal experiences resulted in her scholarly interest and developing the Kubler-Ross Grief Cycle. She describes that there are five stages of grief experienced by those who are dying or grieving the loss: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. I have also experienced several losses, such as the death of my mother when I was 17 years old and the deaths of my three wives. If the grief cycle model existed before 1969, it would have given me a different perspective of the pain I was experiencing while losing the people I loved. Although our theories have different focuses, I realize we share a common interest in adaptability in response to change. Kübler-Ross transformed the attitude toward pain, loss, and death. Meanwhile, I have researched the biological aspect of our brain’s capacity to adapt and learn throughout life.

Donald Schön, a philosopher and professor, taught us that learning occurs when we reflect on it (Clarke, 2024). He was born on September 19, 1930, and died on September 13, 1997. I was 26 years old when he was born. He was also a Harvard graduate. He is known for the theory of reflective practice in which he suggested that we reflect on an experience before and after it has happened. This allows us to learn from it and make more informed decisions. The more we reflect, the stronger the connections are made. His ideas support my theory because, from a neurophysiological perspective, reflecting on what is being learned is essential to forming stronger neural connections.

Diary, sharing my thoughts about these remarkable theorists was an excellent way to better understand their lives and theories, as well as reflect on my own work and life.

Yours truly, Donald Hebb

Engaging with psychological theories and the lives of their authors as one of the most prominent theorists was the most unique and insightful educational approach I’ve experienced. Completing all three steps of the exercise and taking a perspective from the “the history of developmental psychology” enhanced my understanding of the discipline.

I realized that although Donald Hebb’s area of focus was neuropsychology, his work was influenced by well-known theorists who made a mark in developmental psychology, including Sigmund Freud, the founder of psychoanalysis, and Ivan Pavlov, the neurologist and physiologist who described classical conditioning. I recall using the first person voice as Donald Hebb when giving an elevator speech to the first group I was assigned to. Initially, speaking to a group of students from the position of a theorist made me nervous because I always tended to shy away from speaking in groups. It also felt unusual to “be” the theorist. However, this was a great opportunity to leave my comfort zone. Ultimately, the more I used the “I” voice (especially when completing my PowerPoint presentation), the more I started to identify with and see my theorist’s perspective. I pondered upon how he must have felt when his mother died in 1921 when he was only 17 years old. His mother seemed to be a patient and caring woman who loved her son dearly. The Montessori method she used for teaching her son makes me believe that she was someone who wanted her son to grow into a man who appreciated and loved learning. I wondered about how he must have felt when her first wife was killed in a car accident, when his second wife died during an operation, and when his third wife died just 2 years before him. I was in awe to learn how many losses Hebb has suffered yet continued to thrive in his career. I also wondered how he felt when people thought studying the brain was a waste of time. It seems that neither personal losses nor attitudes of some of his colleagues did not discourage him from being productive and continuing his research.

I found this educational experience valuable as it helped me to learn. It has allowed me to develop my technical and creative skills, and I truly enjoyed the process.

Clarke, Daniel. (2024). Donald Shon. LaGuardia Community College, Developmental Psychology (SSY240, Kindred)

Jacome, Katelyn. (2024). Lev Vygotsky. LaGuardia Community College, Developmental Psychology (SSY240, Kindred)

Jordan, Daniel. (2024). B.F. Skinner. LaGuardia Community College, Developmental Psychology (SSY240, Kindred)

Khakimova, Almira. (2024). Virginia Apgar. LaGuardia Community College, Developmental Psychology (SSY240, Kindred)

Kim, Joseph. (2024). Elizabeth Kubler-Ross. LaGuardia Community College, Developmental Psychology (SSY240, Kindred)

Ko, Yun. (2024). Arnold Gesell. LaGuardia Community College, Developmental Psychology (SSY240, Kindred)

Pintado, Elvis. (2024). Sigmund Freud. LaGuardia Community College, Developmental Psychology (SSY240, Kindred)

ACOG Committee Opinion No. 644: The Apgar score. (2021). Obstetrics & Gynecology, 107(5), 1209. https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/committee-opinion/articles/2015/10/the-apgar-score

Hebb, Donald. (1949). The Organization of Behavior: A Neuropsychological Theory. John Wiley and Sons, Inc

Keysers, C., & Gazzola, V. (2014). Hebbian learning and predictive mirror neurons for actions, sensations and emotions. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences, 369(1644), 20130175. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2013.0175