by Dr. Habiba Boumlik (hboumlik@lagcc.cuny.edu)

When colleagues ask about my research interests, I often find myself tracing a path that begins in the alleyways of Morocco, winds through the academic halls of France, and arrives at a screening room in Queens, NY where Amazigh filmmakers share stories that challenge everything we think we know about identity, memory, and belonging. This journey has prepared me for the work I do today: exploring how Amazigh cinema contributes to our understanding of Indigenous peoples and their struggle to control their own narratives.

Growing up in Tangier, Morocco meant living within multiple worlds simultaneously. I was surrounded by the rich tapestry of Amazigh, Arab, French, and Spanish cultures, each with its own language, way of remembering the past, and vision of the future. These cultures contested the same spaces, histories, and claims to authenticity, sparking my earliest questions: Who gets to tell our stories? Whose memories are preserved, and whose are allowed to fade?

These questions traveled with me to France, where I pursued studies in Sociology, Ethnology, and French as a Foreign Language, ultimately earning my Ph.D. in Cultural and Social Anthropology from the University of Strasbourg. France offered me theoretical tools to analyze culture and society, while extensive travels showed me how Indigenous communities worldwide face similar challenges in maintaining their cultural identities against the homogenizing forces of nation-states and globalization.

Eleven years ago, I founded the New York Forum of Amazigh Film, NYFAF, (www.nyfaf.com), which has become central to my scholarly and personal mission. What began as a desire to bring visibility to Amazigh filmmakers in the diaspora has evolved into a platform connecting filmmakers, scholars, artists, and audiences in dialogue about representation, memory, and Indigenous rights.

The New York Forum of Amazigh Film, NYFAF’s team (April 2025): Lucy McNair, co-curator; Habiba Boumlik, founder; Wafa Bahri, social media; Yahya Laayouni, website.

The festival emerged from a simple observation: Amazigh people, despite historically constituting the majority populations across North Africa, remained largely invisible in cinema and academia. When they did appear, it was often through the gaze of others – as exotic footnotes to Arab or French narratives, or as symbols of a timeless, unchanging past. I wanted to create a space where Amazigh filmmakers could present their own stories, in their own languages, on their own terms.

My current research focuses on how a new generation of Amazigh filmmakers is constructing a transnational cinema that serves as "media memory" – a deliberate counter-practice to the erasure of Indigenous memory. Over several years, I interviewed seven filmmakers whose work exemplifies this approach. The results were published in Amazigh Cinema: An Introduction to North African Indigenous Film (2025) edited by my colleagues Yahya Laayouni (Commonwealth University of Pennsylvania) and Lucy McNair (English Department, LaGuardia Community College).

Amazigh Cinema: An Introduction to North African Indigenous Film (McNair & Laayouni, 2025), constitutes the first comprehensive English-language analysis of Amazigh visual media.

These filmmakers navigate the tension between local specificity and global relevance. Ahmed Baidou documents disappearing rituals in Morocco's High Atlas Mountains. Omar Belkacemi creates films in Kabylia that tell universal human stories while facing accusations of separatism from the Algerian state. Wassim Korbi made Azul, the first documentary on Amazigh identity in Tunisia, revealing a hidden community to itself and to the world. Tarik El Idrissi's Sound of Berberia traverses Tamazgha – the Amazigh homeland stretching from the Canary Islands to Egypt – asserting through cinema a geography that official maps refuse to acknowledge.

The diaspora-based filmmakers bring additional complexity. Kamal Hachkar's Tinghir-Jerusalem excavates the lost Jewish past of his Moroccan village, revealing the multicultural history of Amazigh communities. Hakim Belabbes creates hybrid works mixing fiction and documentary from his base in Chicago. Nadia Zouaoui, the only woman among my interviewees, focuses on feminist themes and women's experiences, adding crucial gender perspectives to Amazigh cinema.

My sabbatical research in Morocco and France during Fall 2021 and Spring 2022 revealed five interconnected debates animating Amazigh cinema today.

One of many focus groups with scholars, artists, activists and actors. Agadir, Morocco fall 2021.

First, the language question divides filmmakers. Some increasingly use Darija (Moroccan Arabic) for pragmatic reasons – better diffusion and larger audiences – though this compromises both the Amazigh language and film authenticity while reducing funding eligibility. Others argue cinema has its own language beyond words, rejecting the governmental term "Amazigh-speaking cinema" and noting the irony that films in Darija are simply called "Moroccan cinema."

Second, whether "Amazigh cinema" even exists remains contested. Festival directors insist it's still in early stages, while cultural institute scholars argue that "technically speaking, Amazigh cinema does not exist. We need an industry." They identify three developmental periods: video (1990s), digital transition (2000s), and recent professionalization with films like Adios Carmen and Myopia meeting international standards. Power imbalances persist: Amazigh scripts submitted for funding are evaluated in translation rather than in Tamazight, and festivals seeking support face systematic dismissal.

Third, the political dimension cannot be separated from artistic concerns. Activists draw parallels between Amazigh and women's issues – both become "an annoyance to deal with" rather than receiving genuine commitment. Despite laws requiring 30% Amazigh programming on national channels, compliance remains minimal. The Amazigh movement has paradoxically evolved from an intellectual movement without mass mobilization into a movement without intellectuals. Real change requires political will focused on education, not symbolic gestures.

Fourth, quality versus quantity creates painful trade-offs. Fast production for commercial success undermines artistic quality due to lower funding and technical support. Filmmakers face a dilemma: countryside settings risk reinforcing stereotypes about Amazigh people being frozen in the past, yet market penetration demands increased output. As one actor explained: "If I want to create a fiction film, I don't want to be associated with the past. Therefore, the language is important." Many call for quotas ensuring Amazigh-language films in all genres, including action and contemporary stories.

Finally, standardization versus diversity raises fundamental questions about identity itself. Some filmmakers strongly oppose language standardization, arguing "we are making the same mistakes as with Arabization" and insisting each Amazigh language deserves its own support rather than artificial uniformity. Even debates about the Tifinagh script reveal this tension: while not widely readable, it provides crucial visual identity and recognition.

Tifinagh, the Amazigh alphabet, is now visible on most administrative buildings in Morocco. This photo, taken in a small village in the Atlas Mountains, shows the trilingual signage on a communal swimming pool.

These debates reflect systematic institutional obstacles: inadequate television programming standards, lack of affirmative action despite official language status, absence of Tamazight-speaking evaluators on funding commissions, and discriminatory resource allocation that supports festivals in some regions while dismissing hundreds of Amazigh productions as not meeting "cinema standards”.

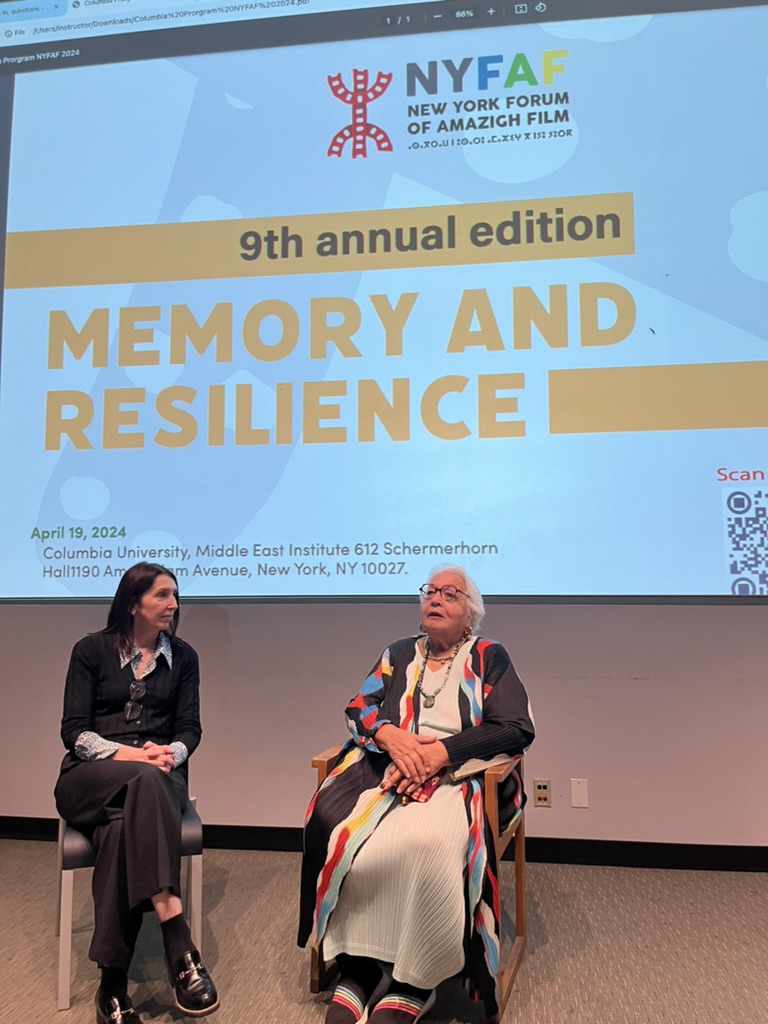

Documentary filmmaker Izza Génini in discussion with Professor Madeleine Dobie at Columbia University, April 2024.

My research positions Amazigh cinema within global Indigenous media studies while documenting its unique transnational character. Like Indigenous peoples in the Americas, Australia, and elsewhere, Amazigh communities have experienced colonization, cultural suppression, language loss, and systematic exclusion from national narratives – facing the imposition of colonial languages (French and Spanish) and dominant ethnic languages (Arabic), appropriation of lands and resources, and denial of their history.

Yet Amazigh filmmakers are part of a global Indigenous media movement that reimagines what cinema itself can be when placed in the service of Indigenous self-representation. What makes this case particularly compelling is its transnational dimension: Amazigh filmmakers spread across multiple nation-states and cannot rely on single national frameworks. Instead, they have built transnational networks of production, funding, and exhibition that bypass national structures.

I argue we must move beyond "national cinema" frameworks when analyzing films created across borders, funded by multiple countries, and addressing audiences spanning continents. These filmmakers use hybrid forms, mixing documentary and fiction, personal and collective history, experimental and traditional techniques. Their formal innovations reflect cultures in transition and ongoing identity formation under diaspora and globalization.

I use "media memory" to describe how these filmmakers function as memory agents, actively shaping what will be remembered and how. In societies where official historiographies have marginalized Amazigh experiences, cinema becomes a powerful tool for writing alternative histories and asserting collective consciousness across generations separated by geography, language, and political borders.

Finally, I document systematic obstacles these filmmakers face: lack of language standardization, funding discrimination, limited distribution networks, absence of professional training programs, and political marginalization that makes cultural expression appear threatening to nation-states. Understanding these barriers reveals how Indigenous communities maintain cultural identities against homogenizing forces while using modern technology to assert both cultural survival and political rights.

Discussion with Florence Martin, professor of Transnational Studies at Goucher College, LPAC April 2025.

Most filmmakers I interviewed resist being labeled "Amazigh filmmakers," seeing themselves as artists concerned with universal human themes. Yet their work collectively contributes to preserving cultural memory, challenging official historiographies, and reimagining pan-Amazigh identity.

The debates I witnessed – about language, standardization, terminology, quality versus quantity and political engagement versus artistic autonomy – reflect a community at a critical juncture. The pioneers who created video films in the 1990s established a foundation. The transitional generation navigating digital technology in the 2000s built infrastructure. Now a third generation faces the challenge of achieving international recognition while maintaining cultural authenticity and creating commercially viable work without sacrificing artistic integrity.

As I continue this work – teaching courses at LaGuardia Community College, curating films for NYFAF, and developing my research – I remain convinced that these stories matter far beyond North Africa. They speak to fundamental questions about how marginalized communities maintain their identities, how memory survives attempts at erasure, and how art can serve both aesthetic and political purposes.

The films screened at NYFAF are not museum pieces or ethnographic curiosities. They are living interventions in ongoing debates about identity, belonging, and justice. They are acts of resistance and imagination. And they remind us that even in our globalized world, local stories – told in languages many have never heard, rooted in histories many have never learned – still have the power to move us, challenge us, and change how we see ourselves and others.

Whether we call it Amazigh cinema, Amazigh-speaking cinema, or cinema of Amazigh expression – the work continues. Filmmakers keep creating despite funding limitations, institutional obstacles, and political marginalization. And scholars like myself keep documenting, analyzing, and advocating – bearing witness to this remarkable moment when an ancient people use the most modern medium to assert their right to be seen, heard, and remembered on their own terms.

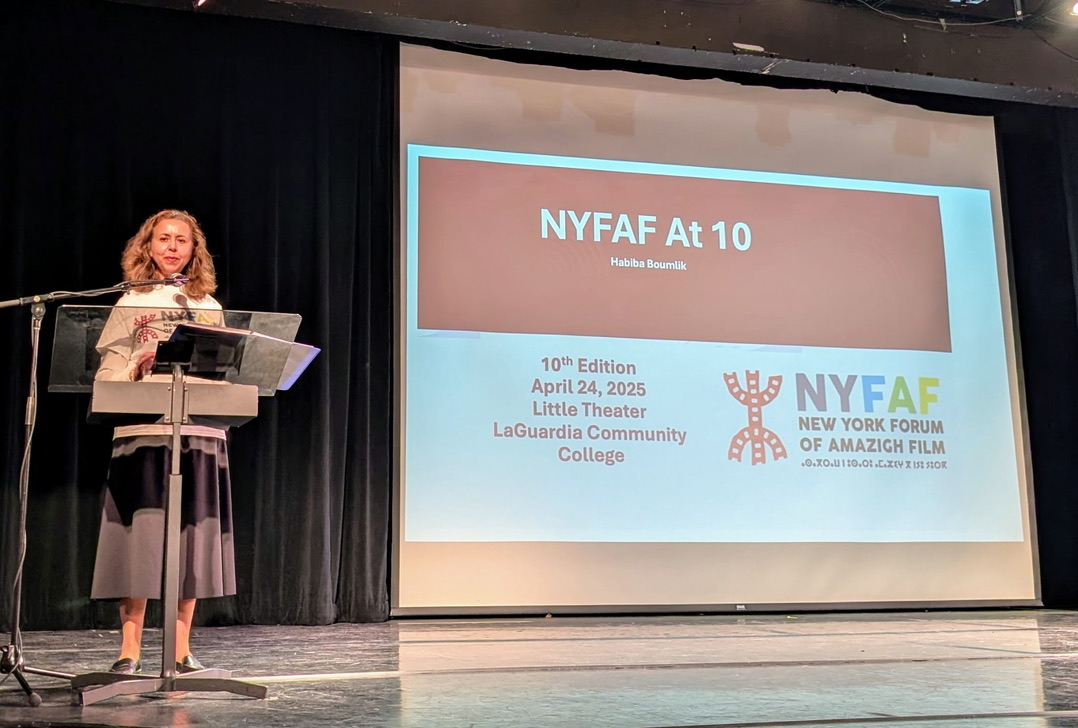

Professor Boumlik recapitulating ten years of NYFAF screenings and film discussions.